Gerrymandering in U.S. elections is a political strategy that allows parties in power to shape electoral districts in their favor. While it might sound like a technical detail, gerrymandering has a deep impact on how democracy functions in the United States. It can determine who gets elected, how policies are shaped, and whether voters feel like their voices actually matter.

This article breaks down what gerrymandering is, how it works, and why it poses serious challenges to fair representation in American elections.

What Is Gerrymandering?

Gerrymandering refers to the practice of redrawing the boundaries of electoral districts in a way that gives one political party an advantage over others. The term dates back to 1812, when Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a map that created a district shaped like a salamander—hence the name “gerrymander.”

In the United States, congressional and state legislative districts are redrawn every 10 years after the national census. In many states, this process is controlled by the state legislature, which often means that whichever party holds power at the time can shape the districts to benefit themselves.

Types of Gerrymandering

Partisan Gerrymandering

This occurs when one political party draws district lines to increase its own political power, often at the expense of the opposition.

Racial Gerrymandering

In this case, district lines are drawn to weaken the voting power of a particular racial or ethnic group. While this form of gerrymandering has been ruled unconstitutional, it still occurs and often leads to legal challenges.

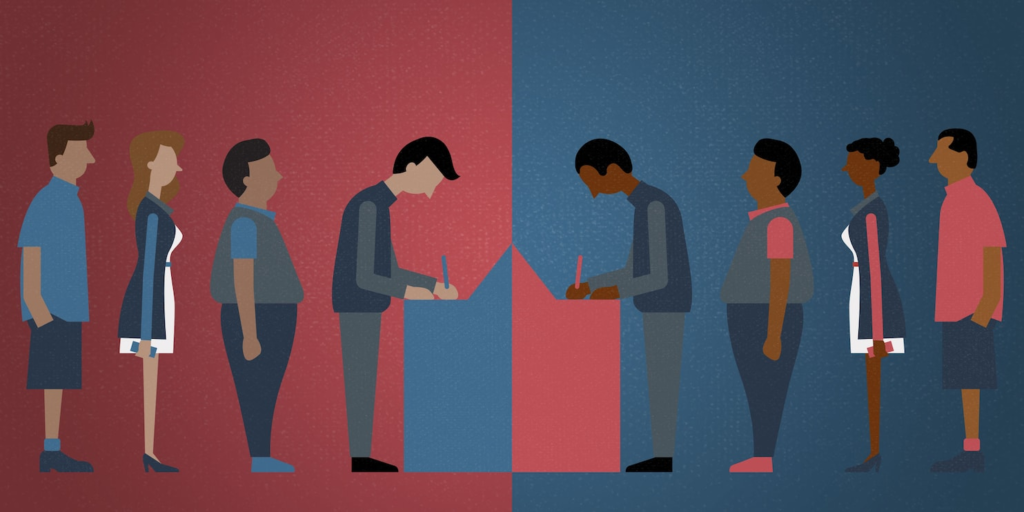

How It Works: Cracking and Packing

Gerrymandering is usually carried out through two main techniques:

Cracking

This method divides a group of voters who tend to vote the same way across multiple districts. As a result, they become a minority in each district and lose the ability to influence the outcome.

Packing

This approach concentrates as many voters of one type into a single district as possible. While it gives them strong representation in that one district, it limits their influence in surrounding areas.

Together, these strategies allow political parties to maximize their electoral advantage while minimizing the voting power of their opponents.

Why District Maps Matter

The U.S. uses a district-based system for most elections, including those for the House of Representatives. Each district elects one representative. If a party can control how those districts are drawn, it can often secure more seats than its actual share of the vote would suggest.

For example, a state might be evenly divided between voters of two parties, but through gerrymandering, one party can end up winning the majority of the seats.

Legal and Constitutional Debate

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional. However, the Court has been less clear about partisan gerrymandering.

In the 2019 case Rucho v. Common Cause, the Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering is a political issue, not one that federal courts should decide. This effectively left the issue in the hands of state governments and courts, which means outcomes can vary widely from state to state.

Real-World Examples

North Carolina

North Carolina is often cited as a key example of partisan gerrymandering. In 2016, Republicans won 10 out of 13 congressional seats, even though the state’s voters were nearly evenly split between the two major parties.

Maryland

In Maryland, Democrats used gerrymandering to create districts that heavily favored their candidates. One district was drawn so irregularly that it wrapped around others, making it nearly impossible for Republican candidates to win.

These examples show that gerrymandering is not limited to one political party. It is a strategy used by both sides when given the opportunity.

Impact on Democracy

Reduced Voter Influence

When districts are designed to favor one party, many voters find themselves in “safe” districts where the outcome is already determined. This makes it feel like their votes don’t matter, which can lead to voter apathy.

Lack of Competition

Gerrymandering often results in less competitive elections. Candidates in safe districts are more likely to win without strong opposition, which means they don’t have to appeal to a broad range of voters.

Increased Polarization

Safe districts also lead to more extreme candidates. In many cases, the real competition happens in primary elections rather than general elections. This encourages candidates to appeal to the most partisan voters in their party, contributing to political polarization.

Weakened Public Trust

When people believe that elections are rigged or unfair, trust in government declines. Gerrymandering feeds this distrust and makes people less likely to participate in the democratic process.

Reform Efforts

Despite these problems, some states have taken steps to address gerrymandering.

Independent Redistricting Commissions

Several states have created independent commissions to draw district lines. These commissions are designed to be nonpartisan or bipartisan, reducing the influence of political parties.

States like California, Arizona, Michigan, and Colorado have adopted this approach. Early studies suggest that these commissions lead to fairer maps and more competitive elections.

Court Challenges

In states without commissions, courts have sometimes stepped in. For example, Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court ordered new congressional maps in 2018 after finding the old ones to be too partisan.

Ballot Measures

In some states, voters have taken the issue into their own hands by approving ballot initiatives to reform how districts are drawn. These efforts show that there is strong public support for fairer election systems.

Role of Technology

Modern technology has made gerrymandering both easier and harder to control. Political parties use advanced mapping software and voter data to draw districts with incredible precision. However, the same tools are now being used by watchdog groups and researchers to expose unfair maps and push for reform.

A Global Perspective

Gerrymandering is largely a U.S. issue. Many other democracies use systems that avoid the problem altogether. For example, some countries have independent commissions that draw district lines, while others use proportional representation, where the number of seats won matches the percentage of votes received.

What Voters Can Do

Although voters can’t draw district maps themselves, they can play a role in fighting gerrymandering. Here are a few steps:

- Support redistricting reform in your state

- Stay informed about how district maps are drawn

- Vote in local and state elections, where redistricting decisions are made

- Join advocacy groups that promote fair elections

Conclusion

Gerrymandering in U.S. elections is a significant threat to fair representation. It allows politicians to choose their voters instead of the other way around, weakening the foundation of democracy. While reform is challenging, it is possible—and necessary. A more fair and representative system benefits everyone, regardless of political affiliation.

Do Follow USA Glory On Instagram

Read Next – Artificial Intelligence in Everyday Life: Explained Simply